Classics Beyond Borders

Written by Dr Frisbee Sheffield, Faculty of Classics, Cambridge

With the support of the Cambridge-Africa Alborada Research Fund and the Leventis Foundation, the Faculty of Classics has established a collaboration with Classicists at the University of Ghana.

Establishing collaborative links with universities across the world, particularly in parts of the world that were formerly under British rule, forms a crucial part of attempts to reclaim Classics from its colonial legacy and reinvigorate the discipline. Classicists in Ghana are at the forefront of liberating the subject from its colonial past and Ghana remains the only country in West Africa where Classics is studied in two public universities (the University of Ghana since 1948, and the University of Cape Coast since 1963).

The Collaboration so far

We have collaborated on a core research project: “Plato and Political Community” by means of a hybrid seminar and two conferences. There are many scholars working on Plato in Ghana; as Professor Ackah argues, Plato is read as “especially relevant” to discussions of leadership, community building, and the welfare of citizens.

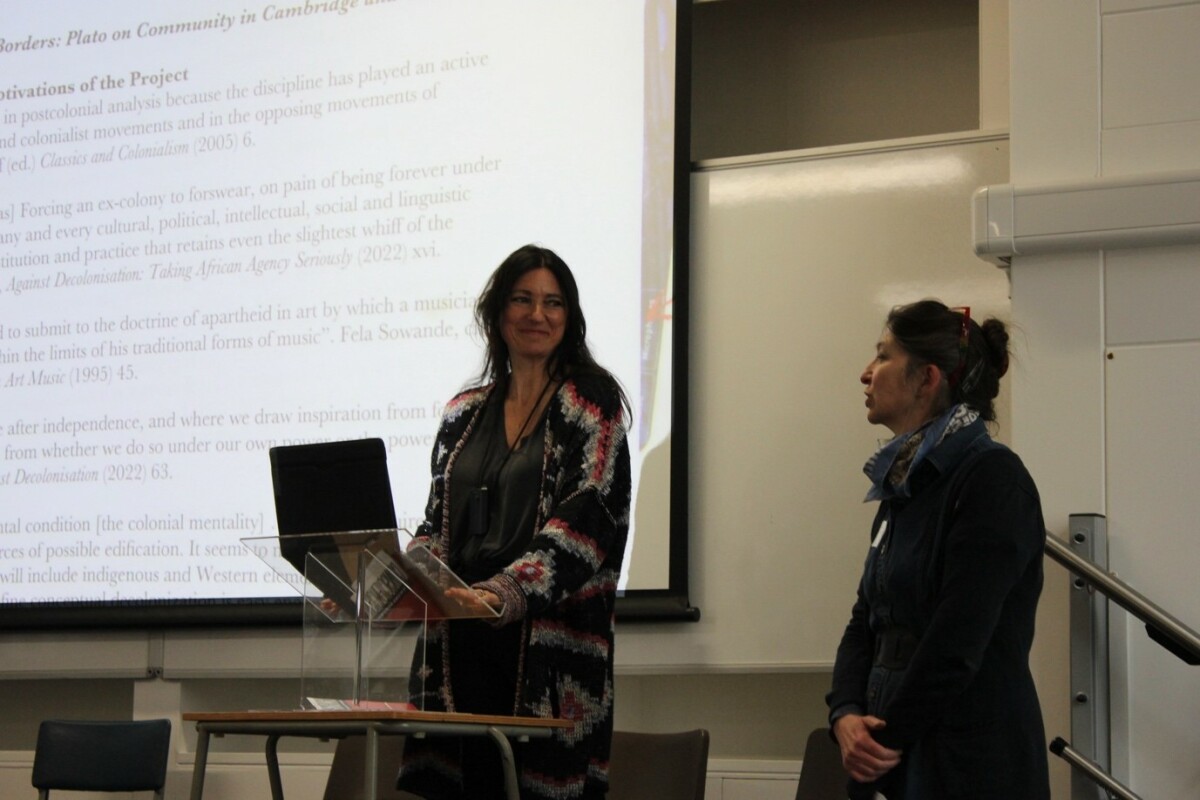

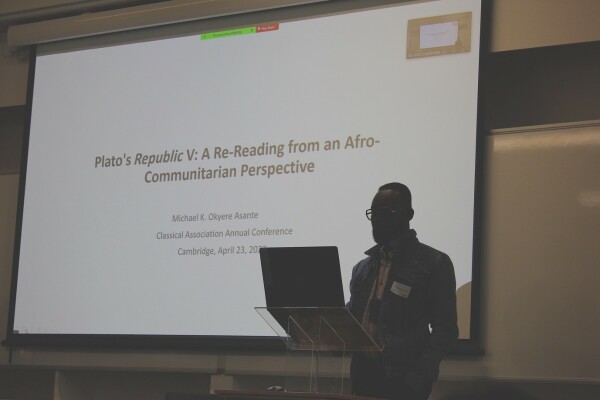

We showcased the first results of this work at a successful panel presentation at the annual Classical Association conference 2023. Two papers from Cambridge scholars and two papers from colleagues from Ghana were delivered on the topic of Plato and community. We presented new work on leading African philosophers, such as the writings of the first president of Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah, who engaged extensively with Greek philosophy, and leading exponents of modern African Philosophy, such as Kwame Gyekye and Kwasi Wiredu.

In September 2023 scholars from Cambridge travelled to Ghana for a further workshop on “Plato on the Nature and Value of Political community”, where we were able to develop the perspectives gained from the collaboration and forge future plans. This includes supporting Ghana’s efforts to establish itself as a centre for Classics in Africa.

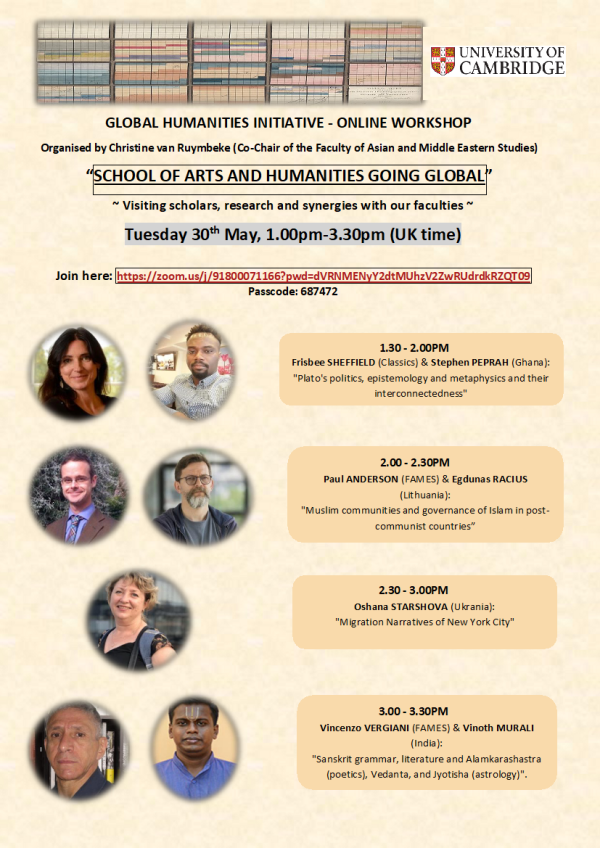

Other aspects of the project include supporting the work of Stephen Oppong Peprah who has a fascinating project on the Anton Wilhelm Amo (1703-1759), a Ghanaian philosopher who wrote philosophical treatises in Latin. Amo was reputedly the first African to study in a modern European University, after he was taken as a boy from West Africa to Amsterdam. Stephen has been working closely with Classicists in Cambridge to offer a new translation of Amo designed to make his works accessible to a wider audience, especially to Ghanaian students and researchers. Stephen presented his work at the Global Humanities Initiative conference. He went on to secure a prestigious award from the British Academy to develop this work.

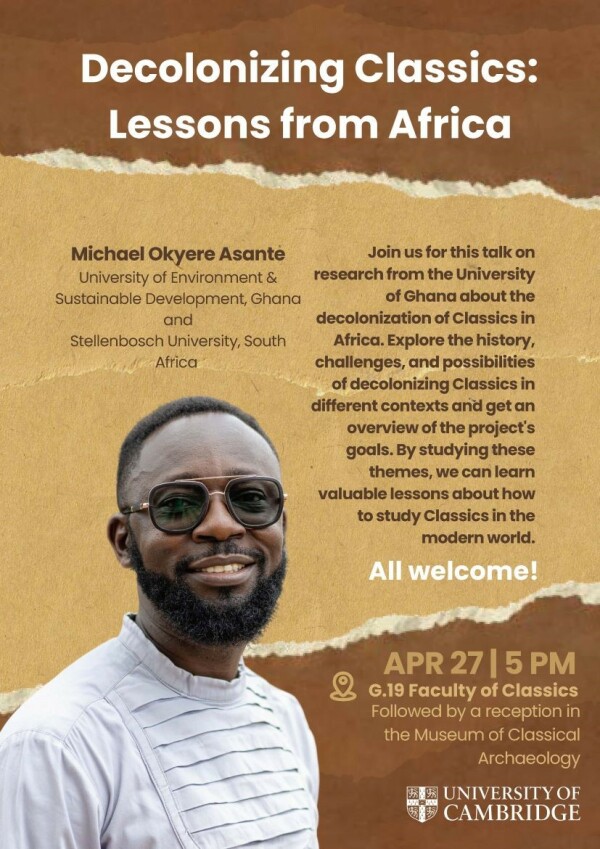

We also hosted a Ghanaian academic visitor, Michael Okyere Asante, Assistant Lecturer at the University of Environment and Sustainable Development, Ghana and The Lisa Maskell Fellow at Stellenbosch University, South Africa, who gave a lecture on decolonising Classics in African universities.

Since Classical languages remain one of the biggest barriers for African students seeking admission into UK graduate programs, we also provided online teaching provision in Greek and Latin, to support the re-introduction of Latin and Greek at the University of Ghana (twice-weekly classes via Zoom).

Lessons so far

Work by Ghanaian Classicists shows that recent calls to decolonise Classics are not a recent, or a UK based, phenomenon. Any such efforts on our part should be considered not only in terms of the presentation of Classics in the UK, but also in terms of those communities across the world who have already been meeting this challenge.

Learning how Classical texts are read by thinkers like Nkrumah and Wiredu provides an opportunity to consider more consciously the social and historical embeddedness of our own work and expose the contingency of our own readings. As we have learnt from our collaborative reading of Plato’s Republic, for example, students and scholars in the US and the UK often read this work under the dark shadow of the Second World War and Karl Popper’s famous critique in The Open Society and its Enemies which cast Plato as a proto-totalitarian figure. Colleagues in Ghana do not operate under this scholarly shadow. They have a rich tradition of Afro-communitarian philosophy, and drawing on the work of philosophers such as Kwasi Wiredu and Kwame Gyekye has provided an alternative framework in which to explore community-building in Plato’s Republic.

Further, responding to the interrogation of the place of Classics in postcolonial Ghana led to a distinctive focus on the relevance of Classical works. To justify its continued inclusion on the university curriculum after independence, Classics had to be shown to be relevant to issues of post-colonial development. Texts we have read as part of this collaboration, such as Plato’s Republic are considered to be an example of ‘practice-relevant thinking’, important, as Professor Ackah argues, to informing discussions of leadership, community-building, and the welfare of citizens. This approach lends the study of these works a vitality and dynamism to offset claims that Classics is ‘elitist’, ‘colonial’ and just ‘ancient’.

Our project partners in Ghana seek to establish Ghana as a centre for Classics in Africa, with an annual conference bringing together scholars from across the continent and, in time, a journal focused on Classics in Africa. This coming September Classics Beyond Borders is supporting a Classical Association Conference in Africa to bring together scholars from across Africa, with colleagues in the US and the UK. A flagship publication provisionally titled: Classics Beyond Borders: Lessons from Ghana will enable us to showcase the perspectives that have arisen in communication with colleagues in Ghana and to disseminate such work to other scholars and students in the UK and beyond.