Dendrochronology Workshop in Zambia by Paul Krusic

Thanks to the ALBORADA Fund, my co-organizers and I are facilitating an African Field School focusing on the science of Dendrochronology. Dendrochronology utilizes annually resolved measures of tree-growth to extract and interpret, and in some cases reconstruct, the environmental conditions experienced by a tree. Many a dendrochronological study has been used to reconstruct climate over that past millennia and further, particularly in the Northern Hemisphere. These reconstructions have provided valuable evidence of global warming, and other anthropogenically induced climate change phenomenon (e.g, extreme drought, hurricanes, and heat waves). However, in the Southern Hemisphere, particularly on the continent of Africa, we suffer from a dearth of dendrochronological evidence as little has been done in terms of identifying tree species that produce annual rings from which reliable chronologies of present and past tree growth may be produced. Our Field School represents a significant first step in addressing this disparity, by bringing students and researchers from sub-Saharan Africa together with experienced dendrochronologists from Zambia, the US and UK, to learn all the necessary theory and methods to conduct sound Dendrochronological studies of their own, and contribute to global knowledge.

Group leaders (left to right); Paul Krusic Dr. Charles Mulenga, Professors Speer and Bekker

The format of this Field School follows that of the North American Dendroecological Fieldweek, a program I started in 1990 and continues to be offered every year. On the first day of the field school, participants are introduced to the various projects offered. This year in Zambia the projects offerings are four:

Tree Anatomy and wood identification group (pictured left) led by Dr. Matt Bekker, Brigham Young University, USA. Participants in Matt’s group will learn how to sample and prepare anatomical microscope slides from various tree species to aid wood identification, a valuable skill for regulating exports, equally valuable to dendrochronologists wishing to know which tree species produce annually resolvable rings!

Tree Anatomy and wood identification group (pictured left) led by Dr. Matt Bekker, Brigham Young University, USA. Participants in Matt’s group will learn how to sample and prepare anatomical microscope slides from various tree species to aid wood identification, a valuable skill for regulating exports, equally valuable to dendrochronologists wishing to know which tree species produce annually resolvable rings!

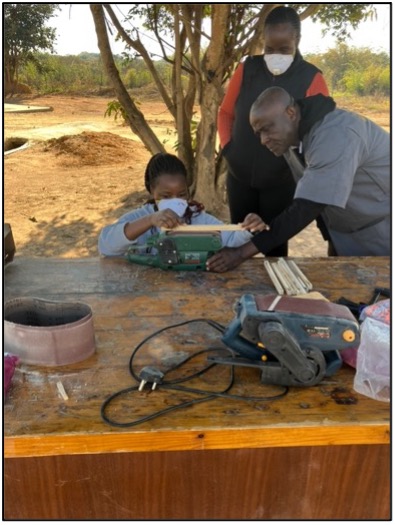

Dendro-Chemistry (pictured left) led by Dr. Charles Mulenga; Copperbelt University, Zambia, will sample trees proximal and distal to one of the many smelting mines in the neighborhood to build chronologies of the elemental content in the wood using a portable hand-held (x-ray florescence) XRF detector to know if particulate pollution from the smelting of ore makes it into the soil and the wood in trees.

Dendro-Chemistry (pictured left) led by Dr. Charles Mulenga; Copperbelt University, Zambia, will sample trees proximal and distal to one of the many smelting mines in the neighborhood to build chronologies of the elemental content in the wood using a portable hand-held (x-ray florescence) XRF detector to know if particulate pollution from the smelting of ore makes it into the soil and the wood in trees.

Dr. Jim Speer, Indiana State University is leading the Dendro-Ecology group (pictured left). His group went deep into the Miambo forest 15 kilometers away to establish a series of plots on which they measured all the vegetation and cored all the trees above 10cm in diameter. From the data and samples they collected, they will attempt to reconstruct the ecological history of the forest, and hopefully determine the pace of natural succession and disturbance. Such studies help identify when an association of plant forms and species has been affected by humans.

Dr. Jim Speer, Indiana State University is leading the Dendro-Ecology group (pictured left). His group went deep into the Miambo forest 15 kilometers away to establish a series of plots on which they measured all the vegetation and cored all the trees above 10cm in diameter. From the data and samples they collected, they will attempt to reconstruct the ecological history of the forest, and hopefully determine the pace of natural succession and disturbance. Such studies help identify when an association of plant forms and species has been affected by humans.

Finally, my project (below), a straightforward Dendro-Climate study, went to the same Miambo forest to find what we hope were the oldest individuals of three Miambo tree species, Brachystegia longifolia, Brachystegia bohemii and Julbernardia paniculate. Previous studies have shown these three species can produce annual rings that can be cross-dated, measured and combined to produce chronologies. My group is hoping to reproduce these results and if successful, find a statistically significant relationship with climate (precipitation), strong enough to reconstruct back in time, and longer than extant instrumental measurements.

Before venturing off into the forest for sampling Jim’s, Matt’s and my group were “entertained” by the local forester for a health and safety presentation, the main topic of which was snakes, particularly those to avoid.

“I don’t want to scare you but, there are many snakes in this forest. If you are bit by a Black Mamba, say your prayers because the nearest hospital is 20 km away and you only have 15 minutes to live. Wear glasses because if a Cobra spits in your eyes you will be blinded, and if a Little Green Tree Snakes bites you, you have 20 minutes, still not long enough to reach the hospital. And try not to disturb the Pythons. The Pythons here are very large, the largest I have ever seen. I’m not trying to scare you.”

Each project is designed to convey the fundamentals of conducting a sound dendrochronological experiment. Once a participant chooses a project, they stay in the project from cradle to grave, meaning they participate in all the elements of the study including data collection, processing, analysis, and writing a short research style article, preparing and presenting a power point presentation delivered to all participants and invited guests on the final day - tomorrow!

Students learning to use the increment borer, a non-destructive means to acquire tree-ring information in the form of a 5mm diameter core from the bark to the pith (pictured left). Once the core is mounted on a wooden block for safe handling, the x-sectional surface is sanded to a highly polished condition.

Students learning to use the increment borer, a non-destructive means to acquire tree-ring information in the form of a 5mm diameter core from the bark to the pith (pictured left). Once the core is mounted on a wooden block for safe handling, the x-sectional surface is sanded to a highly polished condition.

So as you can imagine we are very busy right now. Nine to ten hour days are the norm. With only breaks for meals, provided by the local culinary school students, and the occasional outburst of music, dance and laughter, it has been an intensely fun adventure. Thanks again to the Cambridge-Africa ALBORADA Research Fund for providing the necessary assistance to send the 18 microscopes donated by Cambridge University’s Dept. of Geography to Copperbelt University, without which much of the teaching and research performed here could not have been done. These scopes will be put to good use at Copperbelt in extending the educational experience gained to future students of environmental science in Zambia.

So as you can imagine we are very busy right now. Nine to ten hour days are the norm. With only breaks for meals, provided by the local culinary school students, and the occasional outburst of music, dance and laughter, it has been an intensely fun adventure. Thanks again to the Cambridge-Africa ALBORADA Research Fund for providing the necessary assistance to send the 18 microscopes donated by Cambridge University’s Dept. of Geography to Copperbelt University, without which much of the teaching and research performed here could not have been done. These scopes will be put to good use at Copperbelt in extending the educational experience gained to future students of environmental science in Zambia.

Microscopes arriving for the workshop.