Hunting an elusive parasite vector

Joel Ltilitan Bargul was born in Laisamis in Marsabit County of northern Kenya. This is one of the driest parts of Kenya with a very short rainy season, lasting a few days a year. The land is therefore not arable and the Rendille people, who live here, are nomadic pastoralists keeping mainly camels, goats and sheep. One-humped camels are highly treasured commodities that determine ones’ status among nomadic pastoralist societies of northern Kenya. Camels are prized for their survival in this harsh environment characterized by prolonged droughts. Camels are kept for milk, meat and hides but productivity is constrained by disease and pets, notably ticks and biting flies.

In Laisamis, pastoralists have permanent homesteads where villagers gather in the short rainy season when there is vegetation for the livestock. Once the vegetation dries out, the men and older children take the livestock and travel in search of pastures leaving the women and little children behind.

As a result, children miss out on education. But Joel was lucky because his mother insisted that he went to school, partly as a result of limitations based on tradition.

Joel is the 3rd of 6 siblings. He has an elder brother and sister. What may appear as family trivia has a large bearing on one’s fate in traditional Rendille households. The first son inherits all his father’s livestock and all younger brothers have to work for him or others in the community. Joel’s birth position meant his prospects in life were not great but his mother, who hails from the Samburu community, could not stomach it.

Against her husband’s wishes, Joel’s mother insisted that he should go to school. She walked him the 3 km to school and back at the end of the day. The Catholic sisters who ran the nursery school would motivate parents to bring children to school by providing foodstuffs including rice and cooking oil, once a week.

‘I was out of school for protracted periods of time to engage in livestock herding duties as my father preferred, but my mother ensured I got back. At that time, both parents, like many people in the community, lacked clarity on the importance of education. My three sisters did not go to school as it was perceived to be a waste of money, while my youngest brother had to take over the herding when my elder brother had his leg amputated due to a chronic infection and could not walk far. I am the only one in my family who went to school,’ said Joel.

Joel did not take this opportunity lightly. When he completed primary school and joined St Paul’s secondary school, he worked hard in order to go to university and study medicine. However, it was not to be as he did not get the required marks. He then opted to study Biochemistry at Jomo Kenyatta University.

He emerged top student in the faculty and was recruited as a teaching assistant at the university in 2007. In the same year, he undertook a master’s degree at the Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology (JKUAT) with substantial part of his research project conducted at the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (icipe) and the University of Guelph, Canada. Immediately after completing his master’s, he enrolled for a PhD at the University of Wuerzburg in Germany. For his masters, he conducted research on tsetse flies while for his PhD, he studied African trypanosomes, the parasites transmitted by tsetse flies. After his PhD in 2015, he returned to icipe and applied for a competitive post-doctoral research fellowship known as Training Health Researchers into Vocational Excellence in East Africa (THRiVE).

Dr Joel Bargul in the lab

Joel wanted to build on the foundation he had laid down during his masters and PhD training but he also wanted to work in his home village, where hardly any research is conducted to address local needs. He started by conducting a survey on camel trypanosomiasis and found that about half of the camels in Laisamis were infected with this parasite which causes a disease known as Surra in camels. The strange thing was that in the arid regions of northern Kenya, there are no tsetse flies, which are the definitive vectors of trypanosomes. Joel was therefore keen to know what was transmitting the parasite. For his research, Joel has received funding not only from THRiVE but also from the Cambridge-Africa Alborada Research Fund.

‘The money from the Alborada Research Fund was used to support my field studies and contributed consumables for the research. The work would not have proceeded smoothly without this funding,’ said Joel.

Camel Ked against a pound size coin

To explore the vector for disease transmission, Joel decided to start with what he considered an obvious culprit. Camel flies or camel keds (Hippobosca camelina) are close relatives of the tsetse fly and are plentiful around camels. Joel collected camel blood as well as camel flies from Laisamis and took these back with him to the laboratory in icipe and performed many experiments using laboratory animals.

‘Camel keds seemed to transmit other parasites, but not trypanosomes. Despite all my work, we still are not clear on how trypanosomes are transmitted to camels in this area. Though we have hunches, more work is needed to pinpoint exact transmitters. These findings will contribute to disease control and guide policy makers in pest control programs,’ said Joel.

Although he was not making the progress he expected with trypanosomiasis, he had some unexpected and exciting results. Joel found that 9 out of 10 camels are infected with Anaplasma parasites spread by camel keds. Although camel anaplasmosis had been reported in some countries in the Middle East and North Africa, this was the first report of its kind in Kenya. Interestingly, the anaplasma parasites found in these camels share similarity to another that can be transmitted to humans by dogs. Joel hopes to further this research.

Joel’s interests span beyond insects and parasites, he is keen on ensuring that the community understand the research. On field trips, when he bled the camels and found trypanosomes, he would encourage them to have a look through a microscope. It became easier to understand that ‘that thing running around’ on the slide was the parasite that was causing the camels to be ill. Joel and his team ensured that all camels positive for infection were treated.

The livestock farmers were also able to share local knowledge with Joel, introducing him to local insecticides. This is knowledge that he is making use of in his research. They also described a disease, swollen glands syndrome, that led to a short illness resulting in high mortality in camels. This led Joel to conduct a larger study in the wider Marsabit County to try and understand this disease

As part of his fellowship with THRiVE, Joel was expected to pick a high school and mentor students.

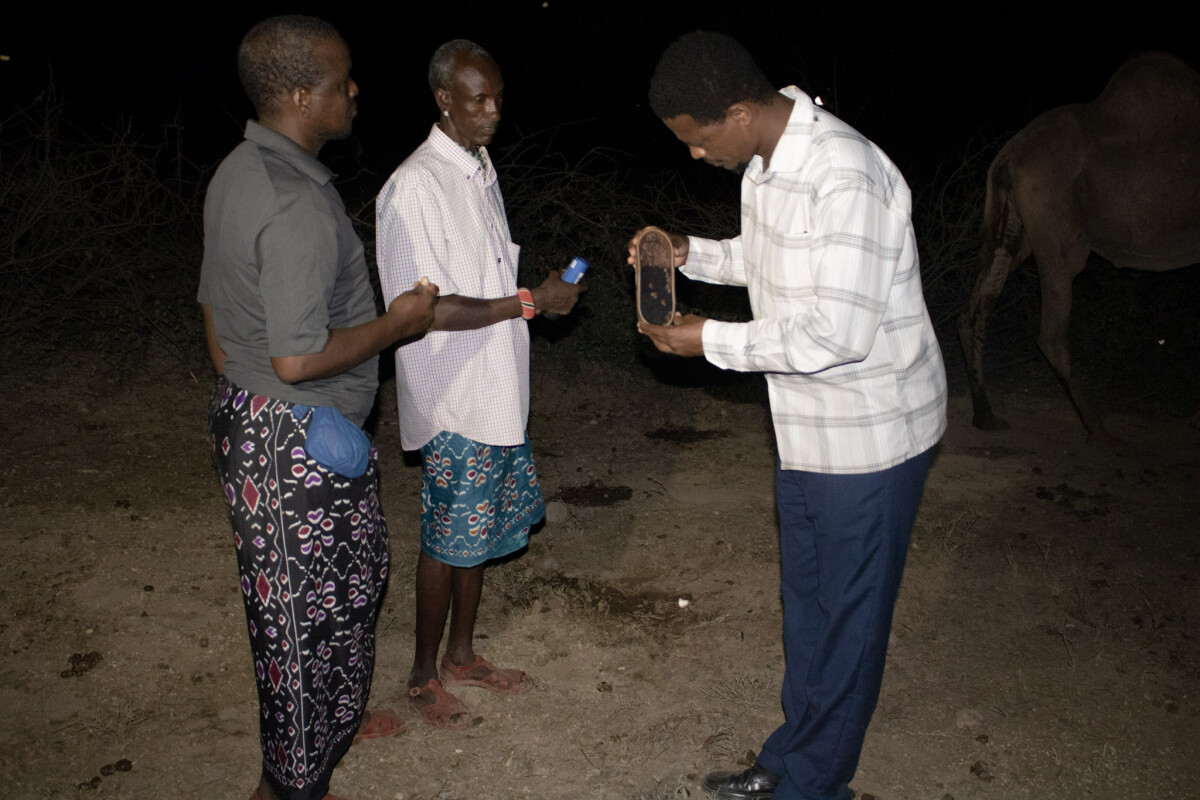

Parents survey to understand their perception on education among pastoralist communities in northern Kenya

'Initially I just did not see the value of it. I was thinking, I am doing research, why do I need to do this as well. But this became a very fulfilling part of my work,’ said Joel.

Joel chose Laisamis Secondary school and has been engaging students with issues on career choices, taking them to collect samples in the field and showing them how their biology lessons translate to practice. Through interaction with the students, he was also able to raise money for books, sports equipment and sanitary towels which were all hindrances to school achievement and attendance

Joel is full of ideas about the work he wants to do next. In the early part of this work, Joel was able to identify three different types of keds, one specific to camels, another specific to dogs and another that is found in livestock as well as wildlife. He is keen to learn about the diseases that these keds transmit to humans. His next research project, when funded, will focus on both livestock and people.

‘The main issue that faces researchers like me is funding that is long-lasting so that we are not stop-starting our research due to breaks in funding,’ said Joel.

Written by Dr Tabitha Mwangi