Education in the context of multiple crises: reflections from the field

Teachers creating alphabet charts for their classrooms at a training workshop, September 2020

On October 12, 2020, the Adamawa state government directed the immediate reopening of its schools. The announcement marked the end of the six-month closure of all schools across the state (both public and private) due to the deadly COVID-19 pandemic. This was the longest and most far-reaching disruption of schools in the history of this conflict-affected region.

Amidst the ongoing conflict with Boko Haram, a terrorist group whose name loosely translates to ‘Western Education is Forbidden’, the COVID-19 pandemic was fast becoming the biggest threat to education in north-eastern Nigeria. The pandemic added an additional layer of conflict and fragility, rapidly escalating from a health-crisis to one of economic and civil unrest in response to the lockdown measures imposed by the government. In fact, 2 weeks after the reopening of schools, the Adamawa state government would impose a 24-hour lockdown following the mass looting and riots that erupted after the discovery of COVID-19 relief items stowed away in warehouses during the pandemic.

As a development practitioner working to provide education in the region between 2016 and 2021, I had the unique experience of working under the context of two overlapping emergencies: Conflict and COVID-19. In this essay, I briefly discuss the primary issues facing education in emergencies, and how the intercalated crisis of the pandemic exacerbated the education challenges in one of the poorest regions of the world.

A Tale of two regions

First, to understand Nigeria we must understand its North-South divide. With over 10 million children out-of-school, Nigeria has the largest out of school population in the world. However, out of this figure, 69% of these children are located in northern Nigeria. In 2020, Nigeria overtook India as the country with the greatest number of people living in extreme poverty. Once again, out of the 90 million people living in extreme poverty, over 70% of them reside in northern Nigeria. And finally, for the past ten years, the northern region of the country has suffered from a violent insurgency led by Boko Haram which was named the world’s deadliest terrorist group in 2015. Indeed, the most populous region in Africa’s most populous country, is plagued with a plethora of problems. A toxic cocktail of calamity that continues to supress the socio-economic development of the region, and the country by extension.

Whilst conflict and poverty play a key role in the lack of education access within north-eastern Nigeria, cultural attitudes towards formal education, especially for girls, are largely apathetic, with families prioritising informal Qu’ranic education for boys, which fails to provide the technical competencies required for the formal economy, while girls are married off at an early age for cultural and economic reasons.

Prioritising education in emergencies

Amidst the competing humanitarian priorities across the region such as security, poverty and more recently, famine, it is often hard to make a political and economic case for education especially in the midst of conflict where military spending is prioritised. Hence, within this complex environment, education is transformed into a battle for the hearts and pockets of the community, political elites, and donors, respectively.

Therefore, in conflict-affected settings, we find that education is primarily conceptualised to support peacebuilding and post-conflict reconstruction efforts to capture the interest of decision makers. In addition, the concept of behavioural change is a prominent feature of education within these settings. By upholding a curriculum that promotes citizenship, while prioritising the social and emotional well-being of both students and teachers, education is conceived as a preventative measure for violent extremism as demonstrated in my previous work with internally displaced children in 2016, and more recently as part of an ongoing education systems-strengthening activity across Adamawa, Gombe, Borno and Yobe states.

Hence, in times of conflict, education is an inherently social activity comprising engagement at the state, school and community levels. In post-conflict settings, education becomes even more of a contact sport, consisting of regular interactions with key stakeholders for peacebuilding, capacity development, and the co-development of strategic education policies to promote ownership and long-term sustainable development.

So what were the implications of strict lockdown measures on an activity that required such a high-level of interaction? Below, I reflect on the three major challenges introduced by the COVID-19 pandemic drawing on my experience working with schools, communities and administrators in north-eastern Nigeria.

Education Financing

According to the World Bank, the COVID-19 pandemic plunged Nigeria into its deepest recession since the 1980s. Past studies have shown the de-prioritisation of education spending during economic crises, and the Nigerian government slashed the education budget by 55 % in the onset of the pandemic. In Adamawa state, school closures were introduced in March 2020, accompanied by an announcement that the government would be unable to pay teachers’ salaries. In addition, education was side-lined in the country’s COVID-19 recovery plans which focused primarily on building resilient health systems, and providing economic relief for small and medium businesses and vulnerable households. Programme-wise, we were equally affected financially. For instance, as a

Socially distanced training workshop, October 2020

donor-funded project, approval for our costed-work plans were put on hold due to the various uncertainties surrounding the prolonged school closures. Restrictions imposed by the pandemic equally meant resources were diverted to keep both staff and beneficiaries safe, resulting in extra spending on gloves, masks, and hand sanitisers. Finally, limitations on the size of gatherings meant an increase in overhead costs associated with holding repeated training sessions for stakeholders once lockdown restrictions eased.

Stakeholder Engagement

Before the pandemic, we met regularly with education stakeholders at the administrative, school, and community levels. However, the pandemic put a hold on these activities, with some stopping indefinitely. For instance, regular monthly meetings with the education secretaries from 32 local government areas ceased. Further, the lack of connectivity and computing equipment meant these meetings could not occur remotely. These meetings were fundamental in building a coordinated network of education administrators for knowledge sharing, as part of our systems-strengthening approach. Similarly, at the school level, we were unable to reinforce teachers’ learning as on-the-job coaching and mentoring was paused due to the school closures. Community engagement both at the high-level with lawmakers and traditional rulers, and with parents at the local level were halted indefinitely. Community outreach was a key pillar in promoting positive attitudes towards education and increasing school enrolment, especially for girls. Sadly, as demonstrated above, the pandemic exacerbated the already dire economic situation of these communities, and I feared the withdrawal of contact and advocacy campaigns due to the lockdown and distance measures, sent a harmful message: education was no longer a priority. On the other hand, the pandemic widened the socio-economic distance between us and our target communities. For example, whilst development practitioners had the luxury of sheltering in place, beneficiaries on the other hand, were economically trapped by the mobility restrictions imposed, plunging them further into poverty. I sense that even if remote capabilities were available, it would be bad taste to discuss ‘business’ as usual and overlook the economic situation. I slowly began to resign to our fate, questioning the role of education in emergencies such as these, and more specifically, its order of priority.

Sensitisation meeting between USAID-SENSE and the 21 Education Secretaries from Adamawa State, June 2019(author crouched)

Inauguration of the USAID-SENSE project steering committee comprising traditional rulers, lawmakers, and education administrators, September 2019.

Teaching and Learning

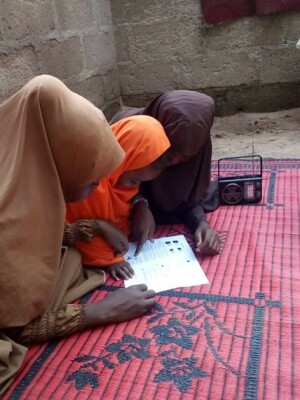

A mother guides her daughters through a literacy radio lesson, 2020

The most immediate effect of the pandemic was the disruption to the learning of both students and the teachers who were trained under our programme. There were fears about the learning loss that would occur during the lockdowns, as well as an increase in drop-out rates following the reopening of schools, with parents opting to send their children to work in order to overcome the economic hardships of the pandemic. Luckily, we were able to leverage our previous experience designing education radio programmes, to quickly mobilise the resources and

partnerships needed to broadcast lessons to over 200,000 children from our target schools. Not every implementing organisation was able to do so. However, recognising that we only worked in about 10% of the schools within the region, this interim intervention was not representative of the learning experience for millions of children during the pandemic across the region, some who attended schools that could not be included in our physical interventions due to security and accessibility reasons.

Social distancing was nearly impossible once schools reopened due to large class sizes, October 2020

Conclusion

As demonstrated above, the COVID-19 pandemic threatened three key pillars of our intervention: financing, collaboration, and capacity development, which are instrumental for rebuilding an education ecosystem that had been damaged by years of conflict. Further, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the gross inequalities that exist in Nigeria, one that I argue is the root cause of the violent conflict that has emerged in north-eastern Nigeria today. This raises further questions on how education can and should be delivered in complex emergency settings wrought with poverty, violence, and harmful ideologies. If education can promote peace and positive behavioural change, then what about economic relief? And what level should be prioritised (primary, secondary or tertiary)? One key take away is that we cannot separate education from the economic realities of the communities we operate in, this holds true both in times of peace and more so in crisis.

Written by Kenechukwu Nwagbo

Cambridge-Africa PhD scholar

This article was first published as a PEER Network blog